How finding your actual client requires investigative work

By: Tina Simpson, JD, MSPH, Co-Founder, Line Axia

This is article #3 in our Field Guide for EU Founders series. Check out the first two here: #1 Strategy without Context, and #2 How Context Defines Opportunities

The United States healthcare system is, first and foremost (and despite significant public funding), a “free” market system.

To illustrate that, lets look at the numbers:

- Roughly half of Americans get their health coverage through employer-sponsored private insurance.

- Another twenty percent are covered by Medicare—increasingly administered through private Medicare Advantage plans.

- Twenty percent receive coverage through Medicaid, the vast majority delivered through privately managed Medicaid MCOs.

- The remainder are covered through individual market plans or are uninsured.

Even programs that are publicly funded flow primarily through private market mechanisms. Medicare Advantage plans manage 54% of Medicare beneficiaries. Medicaid MCOs serve 72% of Medicaid enrollees. Public dollars, private delivery.

This means that to understand how the US healthcare market functions, how purchasing decisions get made, how value is defined, how solutions get adopted—you need to understand it through a payer-driven lens.

In most European systems, a single-national or regional payer sets the rules. Providers navigate one set of regulations, one reimbursement structure, one definition of value.

The US operates differently: dozens of payers, each with their own contracts, metrics, and incentives… and this is true for the small family doctor operating independently to the specialist operating in a health system. This is what we mean by “payer-driven”—not that someone pays for care (that’s universal), but that the fragmentation of who pays fundamentally shapes how the market functions. Different payer types and contracts have different rules, risks, and rewards.

For example, that includes different:

- Decision-making processes and purchasing authority

- Reimbursement models and payment mechanisms

- Regulatory oversight and compliance requirements

- Quality metrics and performance incentives

- Definitions of value and return on investment

A U.S. healthcare provider doesn’t manage “patients” in an undifferentiated sense. They manage multiple distinct populations, defined by payer contracts, with varying rules, metrics, and financial incentives.

A U.S. healthcare provider doesn’t manage “patients” in an undifferentiated sense. They manage multiple distinct populations, defined by payer contracts, with varying rules, metrics, and financial incentives.

A primary care practice will simultaneously manage patients covered by three different commercial insurance carriers, traditional Medicare, two different Medicare Advantage plans, their state’s Medicaid program, and various individual market plans. Each represents a different “mini-business” with different contractual obligations, documentation requirements, quality measures, and reimbursement structures.

This means that when evaluating a digital health solution, U.S. healthtech buyers ask a fundamentally different question than their European counterparts. Not simply: “Does this improve care quality or operational efficiency?” but rather: “Does this improve care quality or operational efficiency in a way that aligns with the specific contractual obligations, financial incentives, and quality metrics we are managing across our payer mix?”

A solution that delivers tremendous value for providers managing Medicare Advantage populations may be irrelevant to providers primarily serving commercially insured patients under fee-for-service contracts.

The same clinical problem can represent entirely different business problems, and advantages, depending on the payer context.

But, Operations are Provider-Driven

Following the money tells you where financial pressure and purchasing power live. But it doesn’t tell you the whole story.

Healthcare is ultimately delivered by providers, physicians, nurses, administrators, care coordinators, and the practices, hospitals, and health systems they work within. Clinicians operate within specific organizational structures and clinical workflows. Understanding how care is organized, who controls operational decisions, and what constraints providers face is equally critical.

This creates a fundamental tension in the US market.

The market is structurally payer-driven in terms of money flows and purchasing authority. But it is operationally provider-driven in terms of care delivery and solution adoption.

Financial incentives may flow from payer contracts, but the day-to-day reality of healthcare delivery is controlled by providers managing clinical workflows, patient relationships, and operational constraints.

This means your economic buyer (the person with budget authority and decision-making power) may not be the same person who will use your solution day-to-day. And the person who uses it may not be the person whose operational reality determines whether it gets adopted into actual workflows. (And we return to the complexity created by fragmentation).

This split is where many solutions, especially those built outside the US context, fail.

Case Study: DocuAide Enters the US Market

Consider a hypothetical example: DocuAide, a clinical documentation tool developed in Germany.

DocuAide uses ambient AI to capture patient encounters and generate clinical notes, reducing documentation time by roughly 40%. In Germany, the value proposition is straightforward: physicians spend less time on paperwork, more time with patients. Practice efficiency improves. Physicians are happier. The ROI is clear.

An American practice administrator hearing the same pitch asks different questions:

“Does it improve my HCC coding accuracy for my Medicare Advantage contracts?”

“Does it improve my HCC coding accuracy for my Medicare Advantage contracts?”

“Will it reduce claim denials from Aetna?”

“Can it capture the quality measures I need to report for my MSSP ACO?”

“Does it integrate with my EHR’s revenue cycle module?”

Same product. Same core functionality. Completely different evaluation criteria.

Why the complexity?

Because, again, in the US, that practice doesn’t manage “patients”; it manages business units and contracts. To collect and defend claims paid to a provider for Medicare Advantage patient, the provider needs documentation that captures HCC codes for risk adjustment. That Aetna patient needs prior authorization paperwork. That Medicaid patient’s visit must meet state-specific quality metrics. The same building, same doctors, treating the same conditions, but operating under different requirements.

This workflow problem is shaped by payer requirements.

DocuAide’s founder, Stephanie, might focus on “reducing physician burnout from documentation burden.” This is a real problem. But in the US, physician burnout isn’t the (prioritized) purchasable problem, at least not in most contexts.

The purchasable problem is: “Our Medicare Advantage contract requires accurate HCC coding for risk adjustment, and our physicians are missing diagnoses that cost us $200 per member per month.”

Or: “We’re losing $50,000 a month to claim denials because documentation doesn’t support medical necessity for the commercial payers.”

Or: “We can’t take on more value-based contracts because our current documentation doesn’t capture the quality measures required for performance bonuses.”

The value proposition, therefore, must be framed by payer contract requirements

In addition to this, American clinicians have learned to be skeptical. They’ve lived through waves of EHR implementations that promised to reduce their workload but were actually built to serve revenue cycle requirements. The result is deep skepticism toward “solutions” that don’t clearly address their specific workflow pain points, while also delivering on the financial and compliance requirements that drive institutional purchasing decisions.

The value proposition, therefore, must align with the provider’s operational realities.

DocuAide needs to ask:

- Which payer types does the target practice serve? (Commercial insurance? Medicare? Medicaid? A mix?)

- What reimbursement model governs each contract? (Fee-for-service? Capitation? Value-based arrangements?)

- What specific quality metrics or documentation requirements are contractually mandated? (These vary by payer and by contract)

- How does documentation quality affect the practice’s financial performance under each contract?

The same practice managing commercially insured patients under fee-for-service contracts has different documentation priorities, perhaps focused more on coding specificity to maximize reimbursement per visit, or on supporting prior authorization requirements for certain procedures or medications.

DocuAide’s leadership might assume that if clinicians love DocuAide, adoption will follow. But in the US, clinicians rarely control purchasing decisions.

Budget authority lives with:

- Practice administrators or CFOs (in independent practices)

- Health system IT departments and finance teams (in hospital-owned practices)

- Revenue cycle management leadership

- Population health management teams (for practices taking on risk-based contracts)

These decision-makers evaluate solutions based on measurable ROI: Will this tool increase reimbursement? Reduce claim denials? Improve performance on value-based contracts? Reduce compliance risk? Enable the practice to take on more patients without adding staff?

The decision for adoption, therefore, is not about the actual effectiveness of the product—it’s about measurable financial impact within specific payer contexts.

What This Means for DocuAide’s Market Entry

Before DocuAide can develop a go-to-market strategy, it needs to:

- Define the target payer segment(s): Which types of payer contracts create the most urgent need for improved documentation? Where does DocuAide’s functionality align with contractual requirements and financial incentives?

- Identify the economic buyer: Who controls budget for this category of problem? What metrics do they use to evaluate ROI?

- Map the decision-making unit: Beyond the economic buyer, who influences the purchase decision? (Clinicians, IT, compliance, revenue cycle—each will have evaluation criteria)

- Reframe the value proposition: How does DocuAide support the practice’s ability to succeed under specific payer contracts? What measurable financial or operational outcomes can be demonstrated?

- Understand workflow integration requirements: Different payer contracts often require different documentation elements, coding specificity, and quality measure reporting. Can DocuAide adapt to these varying requirements within a single practice?

Without this foundational understanding, DocuAide risks positioning a solution to a problem that, while real, will have no adoption success in a US market.

The Takeaway

The U.S. healthcare market is not a single system with a single definition of value. It is a collection of thousands of overlapping markets, each organized around different payer types, each with different incentives, metrics, and purchasing dynamics.

For EU founders, this requires a fundamental shift in approach.

It is not enough that your solution “does a thing”—even if that thing demonstrably improves clinical outcomes or operational efficiency.

You must understand how your solution fits within the specific financial and operational context of a defined market segment, organized by payer type.

This means being able to answer:

- Which specific payer contracts does your solution support?

- How does it increase revenue or reduce costs within those contracts?

- How does it fit within existing clinical and operational workflows shaped by those payer requirements?

- Who has budget authority to purchase solutions in this category, and what metrics do they use to evaluate ROI?

The complexity and fragmentation of the U.S. market can feel overwhelming. But this fragmentation also creates real opportunity. Different payer segments have different unmet needs, different levels of competitive intensity, and different willingness to adopt innovation.

The US market rewards this level of focus—and punishes companies that try to sell everything to everyone. Expert guidance is a necessity, not a luxury.

–

If this article resonated with you—or if you found yourself thinking “wait, that’s exactly the conversation we need to have internally”—let’s talk. Line Axia works with European digital health companies navigating U.S. market entry, helping founders recognize blind spots before they become expensive mistakes.

As always, this post was written by a human being! Not AI. ChatGPT was used for final grammar edits and spellcheck.

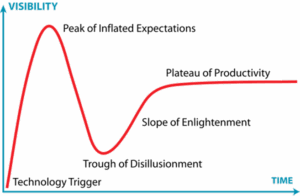

Why the most important innovations are the hardest to fund

Why the most important innovations are the hardest to fund

I use the term ‘ecosystem’ intentionally; and I want to pause and ensure that this Jurrasic-tinged theme hits home before we proceed further. Classifying it as an ecosystem captures the unexpected diversity and adaptation to local conditions that emerges in the absence of centralized authority and intentional design. In the absence of that centralized authority and vision, there is no external force smoothing out variation, aligning priorities, or reallocating resources toward a shared objective. Variation is not mitigated, but amplified.

I use the term ‘ecosystem’ intentionally; and I want to pause and ensure that this Jurrasic-tinged theme hits home before we proceed further. Classifying it as an ecosystem captures the unexpected diversity and adaptation to local conditions that emerges in the absence of centralized authority and intentional design. In the absence of that centralized authority and vision, there is no external force smoothing out variation, aligning priorities, or reallocating resources toward a shared objective. Variation is not mitigated, but amplified.